|

The SS Cities Service Boston was an oil tanker being used during World War 2 to supply the Australian and Allied forces with fuel. Built by Bethlehem Ship Building Corporation Ltd at Sparrows Point, Maryland, USA, for Atlantic, Gulf and West Indies Steamship Lines and launched as the SS Agwipond in April 1921, the ship displaced 8,024 tons and had a waterline length of 141 metres. Its overall length was 146 metres. Lloyds Register says that the ship was powered by a four cylinder steam engine of 636 hp but John Utvich of San Marino, California, who was Commanding Officer of the Armed Guard Unit on board the ship has told me that the ship was powered by a five cylinder triple expansion steam engine (in the configuration O0o0O - where the high pressure cylinder is the middle one and the lowest pressure the outside ones).

Perhaps the ship was re-engined at some time. Mr Utvich also told me that the Boston was a "shelter deck" tanker. That is, she had another deck on the top of the main deck (the tanks were under main deck) and this deck had space for other cargo. In the case of the Boston, she normally carried things like drums of oil for automobiles, sewing machines and other machinery. The ship had been built to serve cities in Africa and India and she operated "like a floating oil market for small cities".

It seems that she may have travelled to New Zealand as on Friday 25 December 1925 the SS Agwipond entered Wellington Harbour. The master was fined £25 (or perhaps £35 - hard to read the newspaper report) for having "the centre loadline disk submerged" (whatever this means).

About February 1929 the Agwipond was purchased by Cities Service Oil Company of USA and renamed. As was normal with Cities Service Oil Company's ships, its name was prefaced with the company name. This was also used by other companies, for example there was a SS Esso Boston. A special survey in July 1932 showed it displaced 9,348 tons but there was no increase in length.

|  |

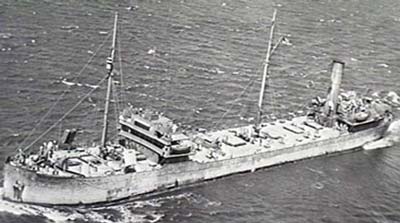

A shot of the SS Cities Service

Boston, possibly on the NSW North Coast | A photo of the gun crew on SS Cities Service Boston |

Requisitioned by the US Department of War Administration for World War II and operated by them until its sinking, the Cities Service Boston travelled to Australia from Los Angeles carrying a load of fuel and oil. More about this later.

The weather for the week around the fatal date was extremely poor and the Sydney Morning Herald reported that the rainfall on this section of the South Coast was said to be the heaviest for nine years.

Although the ship sank on 16 May 1943, the only report of the incident at the time was in the Herald on 19 May when it was reported that four soldiers were drowned when washed off a rock platform on the South Coast. It was reported that eight soldiers were swept into the sea out of 34 standing there. It did not report why they were there or give any explanation as to what happened. Absolutely no indication was given to the fact that a ship was sunk that night.

This was because of wartime censorship preventing most bad news from reaching the public. It is interesting to note that the same edition of the Herald carried the good news of the "Dambusters" which happen only short time before. The same edition also had the bad news of the loss of the hospital ship Centaur on 14 May 1943, two days before the Boston was lost (this made the Japanese out to be heathens for sinking an unarmed hospital ship) and was included for obvious reasons.

No other mention of the wrecking appeared in the media until exactly six months after the wrecking when an article appeared on 16 November 1943 in Sydney's Daily Telegraph actually mentioning the wrecking and the loss of the soldiers. As well as reporting what happened, it reported on the Wollongong Coroner's Court inquiry into the deaths.

From the Telegraph article and visits to the Bass Point area, I knew that what actually occurred was that the soldiers were from a local Army Camp and they had been sent to Bass Point to assist with the rescue of the crew from the Cities Service Boston, but that was about all. I was also aware that while all the crew were saved, the only deaths were four of the saviours.

I was able to find out far more information when I was invited to the 50th Anniversary celebrations of the wrecking held on 16 May 1993. The celebrations were organised by the Six Australian Machine Gun Battalion which was the Army group involved in the rescue. At the memorial service at Bass Point I met Harry Turner (75), Bill Wells (72) and Theo McFadden (72) who were part of the rescue team. I also met Ben Helling (71) of Carmichael near Sacremento, California, who was a sailor on the Cities Service Boston and one of only four known ship crew members to be still alive in 1993.

In April 2001 I was also contacted by John Utvich of San Marino, California, who was Commanding Officer of the Armed Guard Unit on board the ship (see above and references for contact details). The Armed Guards were part of the regular US Navy who guarded all merchant ships in the war. He has sent me copies of the reports he made about the ship's voyage and sinking, as well as copies of some photographs I had not seen before. he has also written to me clarifying some of the things he had told me as well as correctly misunderstandings. The following is mostly based on his reports and emails to me, with some information from Messrs Helling, Turner and Wells.

Mr Helling was an able seaman on his first trip on the SS Cities Service Boston and Mr Utvich was an Ensign in the US Navy, in charge of the Armed Guard Unit on the ship. There were, by my reckoning (based on Mr Utvich's reports), 15 Armed Guards on the ship including Mr Utvich. The Boston had left San Pedro (some reports say Long Beach, they are actually considered the same port), California, on 3 April 1943 at 1200 hours bound for Brisbane, Queensland, carrying a load of diesel and fuel oils (Mr Helling told me it was carrying high-test aviation fuel). The ship was skippered by Captain Anthony Bartolomeo (perhaps Bartholomew). Mr Utvich told me that in his view, Captain Bartolomeo was not a very good Captain as he did not "command" and did not "speak out" for his ship. He also said the Captain had a drinking problem. The First Mate was said by Mr Utvich to be a "school teacher who was not very strong or forthright" and the Second Mate (Navigator) boasted about having his licence suspended several times by the US Coast Guard.

The Boston sailed alone, zig-zagging as she crossed the Pacific. At 1930 on 1 May 1943, when travelling at 9.5 knots (the normal speed), the bow lookout sighted a submarine ahead. However, when the ship changed direction to permit its stern gun (operated by the Armed Guard) to face the ship, it did not appear to Mr Utvich's men that the object was a submarine, appearing to be too high out of the water to be a submarine. The ship was at 26° 49'S 156° 28'E, about 300 kilometres to the east-north-east of Brisbane.

Shortly after this, at 2140, Mr Utvich was called to the bridge and advised that a lookout had contacted the bridge but no voice contact was possible (Mr Utvich's reports continually state that their battle telephones were very fragile and not suitable for use in wet weather). Mr Utvich went aft around this time (he told me midnight) and heard aircraft engines. The plane crossed the ship and dropped a bomb or depth charge about 100 yards off the starboard side. The lookouts and Mr Utvich opened fire with their seven 20 mm machine guns and 50 calibre gun as the plane circled, crossed over the ship and flew away. Mr Utvich told me that this plane was in fact a Consolidated Vultee PBY-5 Catalina Flying Boat of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF). Its pilot and crew were obviously of the view that the Boston was a Japanese ship or surfaced submarine. This incident was also told to me by Mr Helling but I had thought that it was one day after leaving Brisbane. It was also reported in 1979 in an Australian Army publication, confirming it was thought to be a submarine. The ship was at 26° 51'S 156° 30'E (?? - in Mr Utvich's report this was give as 26° 51'S 156° 03'E, clearly an error). The ship continued on a course of 260° true.

The Boston continued and at 0230 on 2 May 1943, a message was received that enemy submarines had been sighted at 26° 57'S 156° 17'E, perhaps 15 nautical miles away. The SS Cities Service Boston arrived at Brisbane at 1800 on 2 May 1943. She discharged her cargo here. While in Brisbane, five additional Armed Guards taken aboard, making a total of 20 on the ship.

At 0800 on 11 May 1943, the SS Cities Service Boston departed Brisbane (empty) as part of an 11 ship convoy (code named PG 50) the Boston then travelled to Sydney with a support of four warships, HMAS Colac, Bendigo, Ballarat and Moresby. At 1420 on 12 May 1943 when the convoy was off Coffs Harbour on the New South Wales North Coast (30° 10'S 153° 23'E), the Japanese submarine I-180 fired two torpedoes. One of the convoy, the Ormiston, was hit by one torpedo. No periscope was sighted prior to this time but a few minutes later a periscope was seen off the Boston's port quarter. Unfortunately, the Armed Guards could not open fire as there was another ship in the line of fire. Five minutes later a small wake was seen in the same area (range 4000 yards) and the guards opened fire with their gun. Three rounds were fired and this was the last of the action.

Despite being hit in the hold, the Ormiston stayed afloat and was still manoeuvrable so it was escorted to Coffs by HMAS Ballarat, arriving in Sydney on 15 May 1943. Another ship, the Caradale, was also hit by a torpedo but it did not explode. The Boston arrived in Sydney at 1830 on 13 May 1943.

In Sydney, three of the Armed Guards were taken off the ship, two for causing friction with the ship's crew and the other for a Court Martial. One other guard went AWOL (absent without leave). Mr Utvich says "These men had been serving [time] in the brig, and were assigned to my ship. They were not the kind of men that the navy needs - Trouble makers". He also told me that they boasted of being in the brig several times and they never changed their ways. Four new Armed Guards came on the ship to take their place. While in Sydney, the Boston is alleged to have taken on 110 tons of grain but Mr Utvich's report says that the ship was empty.

At noon on Saturday 15 May 1943, the SS Cities Service Boston left Sydney in another convoy for Melbourne, Victoria. There were 18 ships in the convoy (Mr Helling guessed 12 to 20), a mixture of types. They were escorted by four warships, reportedly including an Australian destroyer, an American destroyer and a Canadian corvette. The ship was now under charter to the British Ministry of War Transport and after Melbourne, the Boston was to travel alone to Iran. After arriving in Amadan (Abadan), Iran, it was to take on a load of fuel for Madagascar. There were 62 men on board the Cities Service Boston, including as I stated above, 20 Armed Guards.

Leaving the protection of Sydney Harbour, a heavy sea was encountered and during the night, heavy rain fell. Due to the recent active Japanese submarines on the NSW coast, it appears that the convoy was travelling as close to the shore as possible to lessen the chances of being attacked. The Boston, medium ballast, was the lead ship in the starboard side of the convoy. This is, of course, the side closest to the shore. The Captain had set a course of 170° with a 5° leeway. This was to allow for the wind and seas hitting the ship on the port side and forcing it towards the west (towards shore). Considering what happened later, this leeway was obviously insufficient for the weather encountered.

However, Mr Utvich told me that the ship had a very old and obsolete air compass. This was nowhere as good as the liquid compasses that most ships were by then using. When confronted with big seas (such as on this night), the compass's apparent heading varied widely, swinging between two extremes. There was a 100° variation, so to steer 170° the helmsman had to put up with the compass swinging between 120° and 220°.

|

This drone shot shows where the SS Cities Service

Boston hit the rocks |

Mr Utvich says that Captain Bartolomeo told him he was concerned about hitting the ship travelling in the column parallel to the one the Boston was in. This ship was quite visible according to Mr Utvich and even if the ships had got closer to each other in the squalls, it would have been simple to steer away from each other once they eased.

At 0545 on Sunday 16 May 1943, Corporal Fred Tieck was asleep in the Volunteer Defence Corps hut at Bass Point (just to the east of The Gutter dive site) when he was awoken by the man on duty. They could see a light tossing about in the huge seas not far away, but could not understand what could be so close to shore. Soon it was almost level with the hut and then it hit the bombora just offshore. A thing to note is why did it take the Boston so long (almost 18 hours) to travel the short distance to Bass Point? Even at eight knots, it should have only taken about five hours once the Harbour was cleared.

The weather was very bad. Seaman Anthony John Silva was one of the Armed Guards. He was on duty as the starboard lookout, amidships. His report states that "There was a very heavy sea all night, driving rain, high wind, no visibility. Couldn't see the bow or the gun tub 40 feet ahead." He said that he sighted the reef, ran and told the First Mate who ordered hard left and full astern but at 0550 on 16 May 1943, the ship's bottom grated the reef and then hit hard.

|

| The SS Cities Service Boston from the ocean side soon after hitting the rocks |

Mr Helling told me that at 0555 he was thrown out of his bunk in the bow when ship hit the reef. He went up on deck but at first the crew did not know what had happened. They thought they maybe they had been torpedoed considering what had happened only a few days previously. Mr Helling said that he is sure that Captain Bartolomeo knew the ship was mortally wounded and so he drove it further up the reef to avoid it sinking. The ship shuddered every time a wave hit. The waves were so big they were going over the funnel and most lifeboats and rafts were washed away. The crew waited for orders. "We were a goner" said Mr Helling. Assistance was offered by other naval vessels but knocked back by the Captain because of the severe conditions. The Captain gave the order to abandon ship but there was no way they could due to seas and rocks. An SOS was sent by the ship's radio operator, Jay Epstein.

Corporal Tieck could not phone for help as the storm had put the phone lines out. He sent his lance corporal the two miles into Shellharbour to get help. By 0700 Sydney knew of the shipwreck.

The authorities decided to send the Six Australian Machine Gun Battalion to assist from their camp at Dapto. Bill Wells and Harry Turner told me that when the accident happened the majority of the battalion was up in Sydney working on the wharves as the wharfies were on strike. Only a few soldiers were left behind. The train line went right through the middle of the camp at Dapto. The men used to sneak up to Sydney but they had to be back in camp in time for roll-call in the early morning.

|  |

A shot of the SS Cities Service

Boston soon after her wrecking | Another shot of the SS Cities

Service Boston up on Bass Point

soon after the accident |

They said that the group training at the camp before them had created havoc with the Dapto locals causing heaps of trouble. When the Six Machine Gun battalion arrived, they were not well received so they tended to go up to Sydney a fair bit for a drink (plus to meet up with girls).

They used to catch the midnight mail and paper train back on Saturday from Central Station. They used to jump into the empty boxcars and sleep all the way back. As the train went trough the camp, they asked the driver to slow down so that they could jump off easily. Sometimes they had to jump off anyway (the train did not travel too quick). This day they had not too long arrived back from Sydney when they had to go out to Bass Point. They said that they were not asked to volunteer, they were told to get in the trucks and were taken away, not knowing where they were going.

They arrived at about 0830 after travelling through very deep water on the way. There were about 30 or more soldiers and a lot of others (VDC and Police) as well as civilians. They had heavy gear on, ponchos for protection from rain etc.

Another local civilian from Shellharbour, Eric Dunster (?), was driving a milk truck. During break in weather he saw a ship up on Bass Point. He drove out and left the truck near where gates are now into the reserve. He walked out, at 45° due to the strength of wind. Looking back towards Shellharbour he saw there were huge seas hitting the rocks. He got out there about the same time that the soldiers arrived. The rain was horizontal. He helped set up the gear and after a while he left due to the weather.

|  |

The smashed lifeboat with from left,

Gunners S. B. Robinson and B. Shewell and

at right, private W. G. (Bill) Wells

Photo: Jay Epstein via John Utvich | The line to the ship is clearly visible as

a man is brought ashore in the bosun's chair

Photo: Jay Epstein via John Utvich |

Bob Simpson, a local civilian, told me that at 0500 [sic] he heard a siren. There was so much rain there was 3 feet in his front yard. Bill Hovel (a butcher) and he went to the search light battery who were trapped by rain. They got them out after some time. Later a Ford truck came along with 10 men in it. The driver was frozen and could not go any further. Bob could drive a Ford so he drove the truck, which contained some survivors (maybe even including Mr Helling), to get food and warm clothing.

Another of the Six Machine Gun Battalion who attended was Frank Norton. He won an Australian surf lifesaving championship as a linesman (the belt and reel race) in 1939. He was a member of Bronte Surf Life Saving Club in Sydney from 1937 till his death in 2011. He later saw service in New Guinea and Borneo.

On board the Boston, Mr Utvich asked the Captain to put ashore one of the ship's officers to take control of the evacuation but he refused to, talking about the "traditions of the sea" (that is, officers leave last). The ship's second officer was put in charge of the rescue from the vessel's point of view. The bosun lowered one of the starboard lifeboats but it was smashed to pieces in short time. Mr Utvich ordered his men to stay where they were as the ship was not in immediate danger of sinking or breaking up.

He attempted to get a line to shore by tying a lifejacket to a line and throwing it into the sea. Unfortunately it went in on one wave but the next one brought it back. Mr Helling said that it was no use. When the Six Australian Machine Gun Battalion arrived they saw that someone had to jump into water to retrieve the line. In the end, two men from the Six, Lieutenant Sam Matchett (a lifesaver) of Wollongong and Captain Bob Harris (a dentist) of Katoomba, who were champion swimmers, swam out and grabbed the lifejacket.

A bosun's chair was set up with the Australians working in shifts, six pulling the line in and six pulling the line out. First, they pulled the man to shore and then pulled the chair back to the ship. Others were assisting the crew and resting. The crew of the Boston were taken off one by one. It was very hard work, waves were hitting the bosun's chair and sometimes the rescuers. First off the ship were 20 young trainees who were on the ship for part of the trip. Mr Helling was taken off about 20th. It was freezing cold, and the rescuers had blood coming off their hands due to ropes, the boat had started to crack and oil was leaking everywhere. The rain, together with the oil, and the waves made it very slippery and cold. It was also very windy.

The radio operator, Jay Epstein, had a camera with him when he was rescued from the ship and he took some photographs. He apparently sold a copy of each to a reporter for $25 each, totally against the wartime censorship rules! Who said on-the-spot reporting was new?

|  |

Another shot of the rescue

Photo: Jay Epstein via John Utvich | This photo is captioned as Private C. Charters, Gunners S. B. Robinson and B. Shewell,

rescued men and Private W. G. (Bill) Wells at right.

However, I suspect that Shewell is in the chair and this is a re-enactment of rescue

Photo: Jay Epstein via John Utvich |

At one time, one of the lines from the bosun's chair got away and fell into the water and Mr Turner jumped in after it and grabbed the line. Eventually they had got all but two sailors off (maybe four). The tide was coming in, it was almost high tide, and the time was about 1600 or so. A huge wave went right over the ship, maybe two storeys high, and hit onto the rocks. About 12 (maybe) soldiers were washed into the sea. In the oil and boiling seas it was impossible to see what was what.

After the wave, most of the ones washed in clambered out onto the rock platform. Four soldiers died but only two bodies were ever found. After a while the rescue of the two sailors left on the ship was abandoned as it was too dangerous to continue and the boat did not look like it was going to break up now.

Mr Helling was not there when soldiers were swept into sea as he had been taken to dry up and warm up with a cup of coffee. At the same time, Mr Wells was up at the VDC Hut having coffee. He told me that the men would not have had any hope (it was miraculous that the ones got out) as they heavy army gear and the rain ponchos made them very heavy and waterlogged. Mr McFadden said he had just come back to the rescue site from a break at the VDC hut (see later) when the fatal wave hit. "I heard a yell and turned around to see about 10 men being swept into the sea. I started running away but I slipped on the oily rocks and fell over. I was hit by part of the wave". Luckily, Mr McFadden was further up the rock platform and was caught by the end of the wave.

The men who died were:

The above soldiers were awarded The Soldiers Medal by the Government of the United States of America on 4 June 1944. The medals were presented to the mothers of Sergeant Allen, Private Pitt and Private Simmons and the widow of Private Snell at a ceremony in Martin Place, Sydney.

Mr Helling thinks that the ship was the victim of weather, lightness and travelling close to shore. As the storm increased, and due to the threat of submarines, (about 25 ships were sunk off NSW coast during the war) the vessels were given the opportunity to dismiss the convoy and travel close to shore. This is what the Captain of the Cities Service Boston had done.

Mr Helling said that as soon as he was taken off the ship he was taken to a small hut near the bushes at the back of the rock platform. All four agreed that it was just to the east of where the memorial is now. It was presumably the VDC Hut where Corporal Tieck was based. Here he was given a cup of coffee to warm up before being taken in a truck to a pub for a brandy and then to a mission (?) of sorts where they were fed and dried. They were taken up to Sydney the same day. Mr Helling heard about the accident later that day but although he stayed two weeks in Sydney he did not ever get a chance to say thanks to the rescuers. At the reunion luncheon at the Shellharbour Workers Club after the 50th anniversary memorial service at Bass Point, Mr Helling told me that when he went home to US he was interviewed by local paper about the wrecking (he later sent me copies of this).

After the wrecking he went back to the US and then served on another Cities Service Oil ship in the Aleutions, India and South Atlantic. He said he was not involved in any action for which he was glad.

Mr Utvich reported that his group were taken back to the Armed Guard Barracks in Sydney and returned to the Armed Guard Centre (Pacific) at Treasure Island, San Francisco. Mr Utvich was subsequently retrained as a gunnery officer and was assigned to the USS Duffy for the rest of the war. He told me served in Tulagi in the Solomon Islands (see my Solomon Island pages for more information on this place) and he ended up a Lieutenant, US Navy Reserve.

|

| A photo of the wreck shortly before the salvage work started |

The soldiers of the Six Australian Machine Gun Battalion were taken back to their camp but it had flooded and they had no hot water or warm clothes. The publican of the Dapto Hotel invited them there and opened up his rooms and bathrooms for their use. He also threw on free beer. After this, the locals treated them better and when they finally left Dapto for New Guinea, the whole town turned out to farewell the Six Australian Machine Gun Battalion.

When Messrs Wells and Turner were in New Guinea they each received letters from the US Department of War Administration thanking them for their efforts in saving the crew. Mr Norton also received a letter as well.

|  |

| The SS Cities Service Boston some time after the wrecking as some salvage work appears to have started | The wreck and the train track. Note the door cut in the hull |

Mr Wells came down ill in New Guinea with severe acne (possibly a case of allergy) and had to be put out of the army. After spending time in hospital at Goulburn, he spent the rest of the war in the South Head forts and Green Point (near Camp Cove) in Sydney Harbour.

Mr Turner ended up driving trucks and in charge of the motor vehicle pool at North Ryde.

The US Navy put an officer in charge of salvaging things like the Armed Guards guns, armaments and radios as well as certain ships fittings. After the wrecking it was certain that the SS Cities Service Boston would never be refloated as it was high and dry on the large rock platform. I have been told that the ship was stripped of her engines and machinery as well as all fittings.

On 18 July 1945, an area centred on the "hulk" of the wreck was declared as a RAAF bombing range. A circle 1,250 yards in radius was the main section and it extended to the north-east and north-north-west to up past Windang. It was said that "air fighting, gunnery, bombing or similar practice" may take place at any time without any notice. This was revoked on 23 March 1950 along with many other similar bombing ranges.

|  |

| Another photo of the wreck and the train track. | A fair bit of the salvage has been done |

After the war (I think) the hull was then sold to Australian Iron and Steel Ltd (AIS), part of the Broken Hill Propriety Ltd (BHP) conglomerate. I thought till 2023 that the main salvage work on the wreck was done during the war but photos I have now seen seem to show that the work did not start till the early or even late 1950s. There are photos taken in March 1957 and there is still a huge amount of material there.

On 8 January 1944 it was reported in the The Kiama Independent, and Shoalhaven Advertiser that a rail track was to be constructed from near the now location of the toilet block at Bass Point over the rock platform out to the ship. It was forecast that the wreck would be removed in three months. However, this did not happen. Contractors using oxy cutters began dismantling the ship. First to go were the masts, funnel and gun mounts. The deck, interior and hull were then cut into pieces no larger than 16 feet by 7 foot 6 inches. These were then transported by placing on skips that were then pulled along the railway to trucks. The steel was then taken to the Port Kembla steel furnaces (just north of the wreck location) and melted down. The resulting metal was then sent to Whyalla in South Australia to be used in the building of new ships.

A few weeks after the salvage began, heavy seas broke the SS Cities Service Boston in two and the stern section ended up on the bommie. The salvage work continued for several months until what remained was too small to be safely worked on during high tides.

|  |

| The stern of the ship has broken away and is lying offshore | The ship after a good deal of salvage work has been completed

Possibly taken by Bill Campbell, 6 MGB |

On 21 May 1989, the four known surviving [ship] crew visited Bass Point. They were Ben Helling, Ed Webster, John Wirdzek and Bud Rickert.

At the 1993 luncheon, Mr Helling presented Mr Wells and Mr Turner with a medallion each as a token of his appreciation. Mr McFadden had already received his.

As of 2014, there is only one known surviving rescuer, 93 year old Mick Wilkinson.

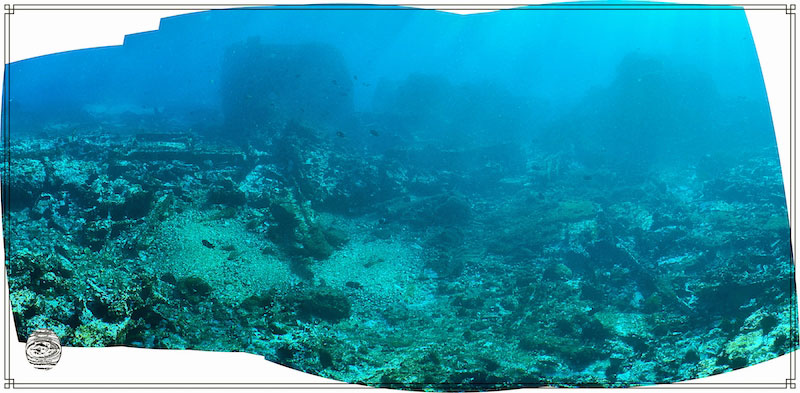

Today, the wreck is almost totally destroyed so that its status as the largest diveable wreck in NSW is not really much to boast as it does not really resemble a ship any more. All that remains are twisted pieces of metal and some bits of the engine and boilers. It can be dived from the shore at the north eastern corner of Bass Point Reserve and part of a boiler can be seen in the surf line from the shore.

More photos at bottom.

References:

MORE PHOTOGRAPHS OF SALVAGE

|  |

| A photo of the prop - 1950 | Another shot of the prop - 1950 |

|  |

A rare colour photo of the prop about 1950

Photo courtesy of Shellharbour City Museum | A closeup of the bow and the train track.

Note the much enlarged "door" cut in the hull |

|  |

A photo of the wreck taken on the deck shortly before

any salvage work started - note the graffiti

Photo courtesy of Shellharbour City Museum | Salvage work is well underway |

|  |

A photo of the bow before the salvage work started

Photo courtesy of Shellharbour City Museum | Some salvage work has been done, the deck is gone exposing the tanks |

|  |

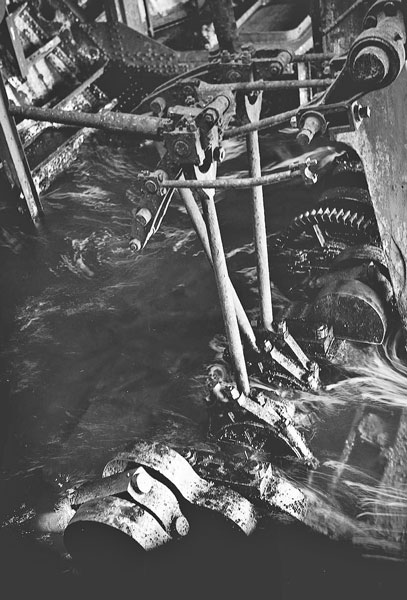

Inside the flooded engine room, 1943

Photo courtesy of Shellharbour City Museum | Inside the flooded engine room, 1943

Photo courtesy of Shellharbour City Museum |

UNDERWATER PHOTOGRAPHS OF WRECK

Courtesy of Craig Taylor.

|  |

| The two boilers | Another shot of the boilers |

|  |

| The engine crankshaft | Not sure what this is |

| |

| A panoramic photograph of the wreck site |

|  |  |  |

|